Confession: I’ve never liked webmail – I was a hardcore Eudora user for ages, then spent five years with BeOS desktop mail clients, then a year with Entourage on the Mac before finally switching four years ago to Apple’s Mail.app, with its flawless IMAP implementation. Every time I’ve tried the “next generation” of webmail clients, they’ve felt anemic to me, and I’ve felt like my workflow slowed way down — not because they were slow per se’, but because of the dozens of small niceties you get with desktop clients that you don’t get with webmail. I’ve relegated webmail to something you use when you’re not at your own machine for some reason and/or aren’t able to take the two minutes it takes to configure IMAP at a foreign machine.

Confession: I’ve never liked webmail – I was a hardcore Eudora user for ages, then spent five years with BeOS desktop mail clients, then a year with Entourage on the Mac before finally switching four years ago to Apple’s Mail.app, with its flawless IMAP implementation. Every time I’ve tried the “next generation” of webmail clients, they’ve felt anemic to me, and I’ve felt like my workflow slowed way down — not because they were slow per se’, but because of the dozens of small niceties you get with desktop clients that you don’t get with webmail. I’ve relegated webmail to something you use when you’re not at your own machine for some reason and/or aren’t able to take the two minutes it takes to configure IMAP at a foreign machine.

That’s why I’ve always been amazed to see how many developers and gear-heads use GMail. These are tech-savvy people, who I’d think would have the same frustrations with webmail that I do. What are they seeing that I’m not seeing? I totally get the convenience factor of being able to access my mail through any web browser, anywhere. I wouldn’t mind having that, but so far it hasn’t seemed worth the sacrifices. I know GMail keeps getting better, so thought it was finally time to give myself over to GMail for a week and see how it goes. Here are some notes on that experience.

That’s why I’ve always been amazed to see how many developers and gear-heads use GMail. These are tech-savvy people, who I’d think would have the same frustrations with webmail that I do. What are they seeing that I’m not seeing? I totally get the convenience factor of being able to access my mail through any web browser, anywhere. I wouldn’t mind having that, but so far it hasn’t seemed worth the sacrifices. I know GMail keeps getting better, so thought it was finally time to give myself over to GMail for a week and see how it goes. Here are some notes on that experience.

n.b.: I’m using Google’s official list of keyboard shortcuts. I used the 3rd party tool A to G to convert Apple’s Address Book to CSV, then imported 1200 contacts into GMail’s contact system.

My list of GMail gripes, with a few faint praises in the mix:

– No way to change the default reading font. Really??? The default reading/writing font is just too small to be comfortable (for me), and it’s ridiculous that something this straightforward and ubiquitous in desktop clients would not be there. How hard can it be to give the user a choice of common font faces and sizes? Does not compute.

– No way to quote previous text before replying. Every desktop mail client I’ve used lets you select a block of text in a message, then hit Reply. Only the selected text appears in the reply. This is so core to netiquette and to my every day workflow that it seems like a non-negotiable feature. And yet no webmail client I’ve tried supports it. Not even GMail. No wonder over-quoting is such a problem these days. Later… OK, I discovered that this “feature” is actually available under Settings | Labs. When I enabled it, it complained that it could “not be loaded,” and continues to complain every time I exit the Settings menu, though it did work correctly in my first test. Cool, but why is it in Labs, as if it’s some kind of optional convenience that only a few people might want? How can this not be part of the default package? Core functionality.

– Inline photos. A family member sent 10 photos as attachments. When viewed in Mail.app they’re displayed inline, nice and large; GMail only shows thumbnails inline, though you can click “View all images” to see them full size on a separate page. There is of course no option to “Save all to iPhoto” in GMail. Since they were family photos, that’s exactly what I wanted to do.

– No preview pane. For realsies? I know of at least two webmail clients (RoundCube, which is available on Birdhouse, and Apple’s mac.com (errr, me.com)). If they can do it, why can’t one of the most popular webmail clients of them all?

– More clicks to view the next message. When done viewing one message, if you click Delete or Archive, you’re taken back to the full message list, which lacks a preview pane. So you then need to click again to view the next message. This kind of “more clicks/keystrokes to accomplish common tasks” is all over the place in GMail.

– No way to turn external mail checking on/off. I now have GMail configured to work as a POP client to two external accounts (would have configured it as IMAP, but GMail doesn’t support that, even though you can use external clients to talk IMAP to GMail – weird). Now I’d like to have GMail stop checking those two external accounts for a while, without removing all the config info. Too bad – the only way to make it stop is apparently to delete the account completely. Grrr…

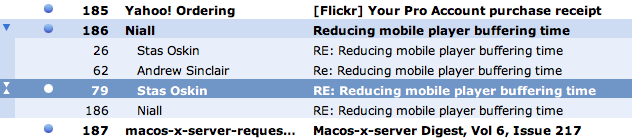

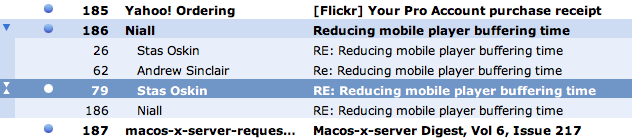

– Poor conversation threading. GMail does an OK job at this – better than other webmail clients, but nowhere near as clean visually or as easy to navigate as threaded discussions in desktop mail apps. And because GMail shows a thread all on one page (thanks again to no preview pane), deleting individual messages out of the thread takes a lot more scrolling and clicking than it does in a desktop client. GMail’s threading is a pale imitation of technology we’ve had on the desktop for years. However, I really do like being able to see my own replies automatically in the context of the thread, even without having explicitly cc:’d myself, and without having to dig through the Sent folder. But the ease of expanding and collapsing a thread, of jumping to the next unread message in a thread, of deleting individual messages from a thread… all vastly superior in Mail.app.

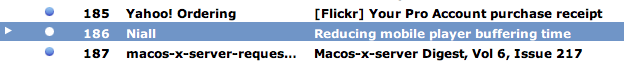

In Mail.app, a thread is indicated by the presence of an arrow in the left column.

Cmd-RightArrow expands the thread; spacebar jumps you to the next unread message in the thread. The actual conversation is shown in the Preview pane. It’s easy to delete individual messages from the thread.

– Keyboard shortcuts. Yes, there are some. Yes, they work for the most part. But they’re not as ubiquitous or as clean to use as the keyboard shortcuts in a desktop client. I found myself doing a lot more mousing in GMail than I’m accustomed to doing in email.

– Adding contacts. I get a message from someone who’s not in my Contacts list. If there’s a way to add this person to my Contacts list on the fly, I’m not seeing it (yes, I looked). Mail.app makes this common process trivial and intuitive.

– Moving messages between accounts. One of the ways I rely heavily on IMAP is the ability to drag and drop messages between various mailboxes and servers. If I receive a message at work that I want to handle at home, I drag it from calmail to birdhouse, and vice versa. If I want to pull something out of cold storage (e.g. from a local mail store and put it back on a live mail server for handling), I can do that. GMail can be configured to talk to multiple accounts, but since it itself does not work like an IMAP client to foreign mail servers, it can’t do any kind of inter-server message moving. I guess the idea is that its model makes this kind of thing irrelevant, but it feels like a big missing piece of the modern mail experience.

– Integrated chat. Both GMail and Mail.app have this, but GMail clearly wins here when you’re at someone else’s computer since you don’t have to set up both the mail and chat clients (thanks @jrue for this point).

– “Send Again” feature. Not something you use a lot, but when you do, it’s a real time saver. Use this after sending a message to someone who’s address has died and you want to try again to the right address, or when you left someone off the original cc: list. Mail.app and other desktop clients have it. GMail doesn’t.

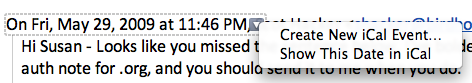

– Breaks quoting. Let’s say you’ve got a paragraph of quoted text in an incoming message and you want to reply to it in two parts. In a desktop client, you put the cursor where you want to break the graf and hit Return. A new quote mark is automatically added to the beginning of the new line. Not in GMail – you end up with the first line that should be quoted suddenly unquoted. Later… turns out this does work properly in rich text mode in GMail, but not in plain text mode. But I prefer to stay in plain text mode, only switching to rich text mode when necessary.

While replying in plain text mode in GMail, insert cursor in the middle of a paragraph and hit Return to start your reply. The new line lacks a starting mail quote mark, breaking netiquette and readability for the recipient.

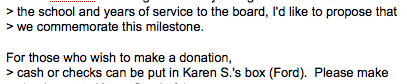

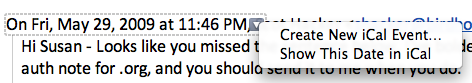

– No Data Detectors. OK, this is only available in Mail.app, not all desktop mail clients, but it really is a killer feature. Roll over any date or time in any format, or any person’s name or email address, even in a plain text message, and you get a little drop-down menu that lets you quickly add that item to your calendar or address book.

Data detectors do an amazing job of figuring out all the right fields — almost magic (try it with messages referencing “tomorrow” or “next Tuesday.”) GMail does have an “Add Event” option but it’s nowhere near as intelligent or as slick, and it works for the whole message, not for individual text snippets within the message. Big win for Mail.app.

– Partial word searches. The search feature in GMail is nice, but is not better than the one in Mail.app. Yes, Google is a bit faster at returning results, but not by much (yes, Apple’s Spotlight is *that* fast). But here’s the kicker – Google and GMail can’t do partial-word searches. So if I’m looking for an email that I know includes the word “question” but I just type “quest” [Return] into GMail search, it turns up nothing! Wildcard searches don’t work either. Very frustrating. Even on their native search turf, Google loses to Apple. Update: There are also types of searches Mail.app can’t do, such as combined OR statements. So let’s call this one a draw.

– End-of-line key combo. On the Mac, the standard keyboard shortcuts to jump the cursor to the start/end of the current line are Cmd-RightArrow and Cmd-LeftArrow. These don’t work in GMail. In fact, as far as I can tell there’s no keyboard short to do this on the Mac in GMail. Which amounts to one more reason GMail is a lot more mouse dependent than using Mail.app or other desktop client. Can’t blame this on rich text editors either — WordPress uses a TinyMCE variant, and Cmd-RightArrow works there just fine. GMail is just broken in this respect.

– Ads in my email. They just bug me. I totally understand that that’s how I pay for the service. I get that. I still don’t like looking at them. Irritating. In fact, I found the whole GMail experience more cluttered and just… less elegant than working with a desktop client.

ADDED LATER

– Multiple windows. Sometimes I like to have two or more messages open at once, plus a compose window, so I can copy/paste bits around and between messages, or for reference while writing something new. Easy to do in a desktop client. Assumed I could do similar in GMail by cmd-clicking messages to open them in various tabs, but nope – GMail doesn’t allow that – forces you to only be looking at one thing at a time. Is that a feature they haven’t implemented yet, or an intentional limitation? Feels like the latter.

Upshot: I didn’t follow through on my promise to try GMail for a week. The frustration was too much to deal with, and I quit after four days. I’m back on Mail.app now. I probably missed out on some of GMail’s goodness, but overall, I left feeling exactly like I did going in. GMail has its advantages, but to me, it seems like they’re vastly outweighed by the absence of basic functionality and elegance present in all desktop mail clients (and by additional features in Mail.app) that I just missed too much. Feels good to be home.

This document aims to lay out what I see as being the pros and cons of two popular web publishing platforms: The PHP-based

This document aims to lay out what I see as being the pros and cons of two popular web publishing platforms: The PHP-based  Recently I was invited to participate in the

Recently I was invited to participate in the Blog look different? At first glance, not by much, but I’ve just completed a massive cleanup of the back-end, replacing the old HTML/CSS with the

Blog look different? At first glance, not by much, but I’ve just completed a massive cleanup of the back-end, replacing the old HTML/CSS with the  Confession: I’ve never liked webmail – I was a hardcore Eudora user for ages, then spent five years with BeOS desktop mail clients, then a year with Entourage on the Mac before finally switching four years ago to Apple’s Mail.app, with its flawless IMAP implementation. Every time I’ve tried the “next generation” of webmail clients, they’ve felt anemic to me, and I’ve felt like my workflow slowed way down — not because they were slow per se’, but because of the dozens of small niceties you get with desktop clients that you don’t get with webmail. I’ve relegated webmail to something you use when you’re not at your own machine for some reason and/or aren’t able to take the two minutes it takes to configure IMAP at a foreign machine.

Confession: I’ve never liked webmail – I was a hardcore Eudora user for ages, then spent five years with BeOS desktop mail clients, then a year with Entourage on the Mac before finally switching four years ago to Apple’s Mail.app, with its flawless IMAP implementation. Every time I’ve tried the “next generation” of webmail clients, they’ve felt anemic to me, and I’ve felt like my workflow slowed way down — not because they were slow per se’, but because of the dozens of small niceties you get with desktop clients that you don’t get with webmail. I’ve relegated webmail to something you use when you’re not at your own machine for some reason and/or aren’t able to take the two minutes it takes to configure IMAP at a foreign machine.  That’s why I’ve always been amazed to see how many developers and gear-heads use GMail. These are tech-savvy people, who I’d think would have the same frustrations with webmail that I do. What are they seeing that I’m not seeing? I totally get the convenience factor of being able to access my mail through any web browser, anywhere. I wouldn’t mind having that, but so far it hasn’t seemed worth the sacrifices. I know GMail keeps getting better, so thought it was finally time to give myself over to GMail for a week and see how it goes. Here are some notes on that experience.

That’s why I’ve always been amazed to see how many developers and gear-heads use GMail. These are tech-savvy people, who I’d think would have the same frustrations with webmail that I do. What are they seeing that I’m not seeing? I totally get the convenience factor of being able to access my mail through any web browser, anywhere. I wouldn’t mind having that, but so far it hasn’t seemed worth the sacrifices. I know GMail keeps getting better, so thought it was finally time to give myself over to GMail for a week and see how it goes. Here are some notes on that experience.