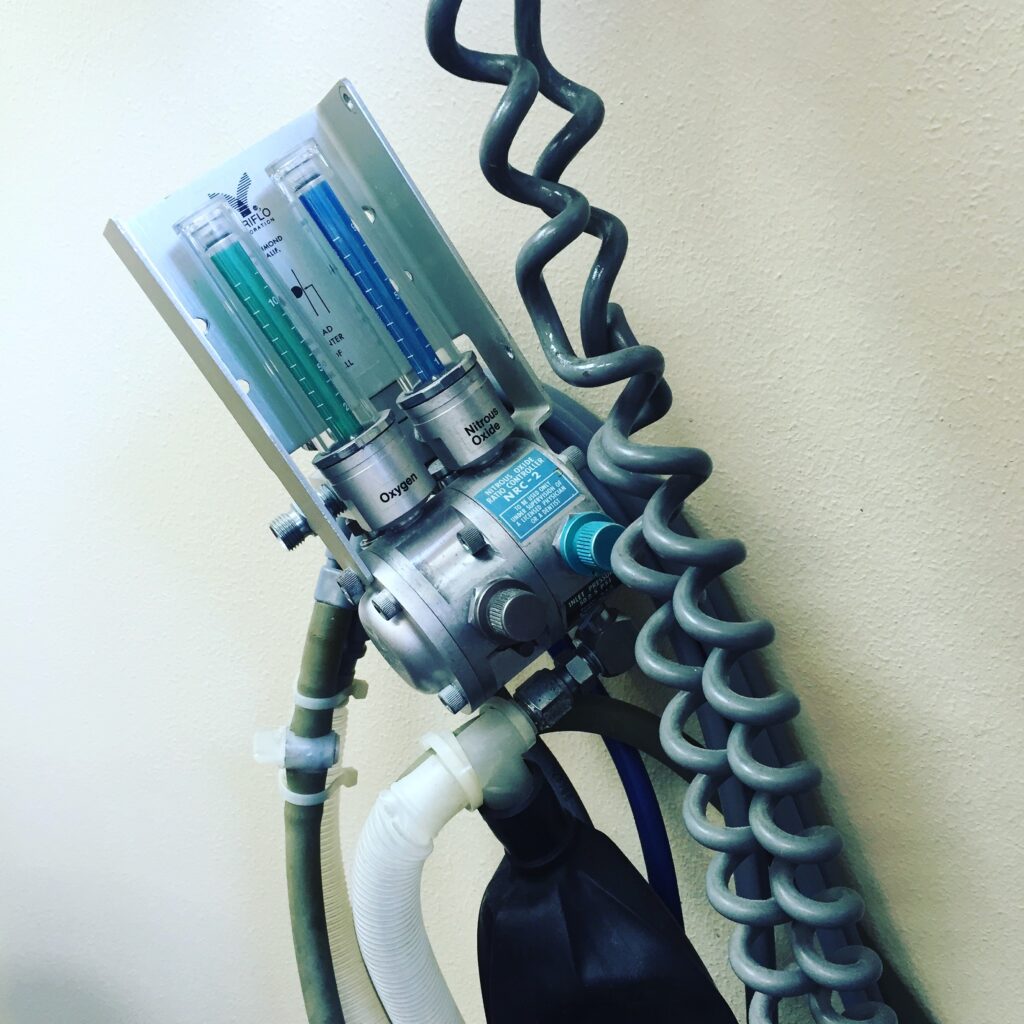

I’ve had three radiation visits and one chemo session so far. It’s hard to separate out what sensations I’m having are the result of what, but I know that I feel a hot tingling in my throat after radiation days, which I take to be the first sparkles of sunburn back there. It’s a minor effect though – no real pain.

It’s harder to describe how the chemo effects feel. Sometimes it feels like I have the beginnings of a head cold, like my sinuses are clamping down, and I have some of the brain fog that goes with a cold. But I’m not sick, and it’s kind of more “penetrating” than a sinus head-cold sensation. I feel like I have to work a bit more to think through the brain fog than I would with a head cold too.

After a few days, some of the initial exhaustion kicked in, and has persisted. It comes and goes, but there’s a noticeable difference compared to usual – even when I get a full night’s sleep, I find myself wanting to nap in the middle of the day, and I’m allowing it.

I have a small flotilla of anti-nausea meds on hand, but have been lucky so far not to experience almost any nausea at all. Some of them are recommended for certain days (“take these on days 2, 3, and 4 after chemo), while others are “as needed.” I’ve only taken one of the “as needed” pills. But it’s early days yet – I won’t be surprised if I need them more in future weeks.

I’m noticing a definite diminishment of my ability to taste food – things that I think of as delicious just … aren’t. I’m not yet at the “wet cardboard” stage that some patients describe – there’s some taste there. But everything feels unsalted when it’s already salted. Fruits taste less sweet. Fats taste less fatty. According to one of the doctors, this is a real challenge for people, who lose all desire to eat when they can’t taste their food, and that’s a problem when it’s critical to keep your caloric intake high. I feel like I’ll be able to stay committed to plentiful eating even if it tastes like nothing.

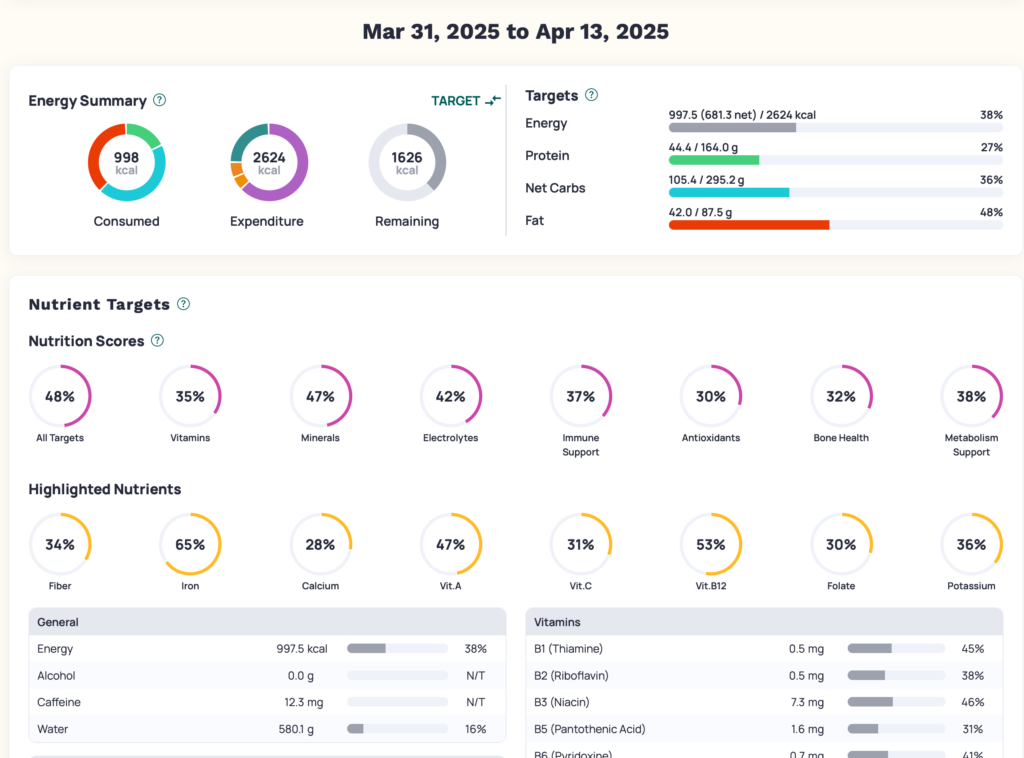

I was advised to start tracking everything eat with a calorie tracker, and chose the badly named Chronometer. It’s kind of fascinating seeing exactly how many prunes it takes to equal the calories in an egg, but it’s a rabbit hole trying to figure out how much detail to go into with your entries. I’m using it in an approximate way, just trying to meet the recommended 2500 calories per day.